The various processes in use during the twentieth century are described in How it Works: Printing Processes, reproduced on the Production Methods page by kind permission of Ladybird Books.

Typesetting

The era of hand composition lasted from Gutenberg’s time until well into the twentieth century for some types of printing, notably jobbing work. Composition is the placing of individual pieces of type, each of which represents a letter, figure, space, punctuation or other mark, into a holder known as the ‘composing stick’, following the hand- (or later type-) written original.

During the mid-19th century, machines to mechanise the process of composing type and redistributing it after use were patented but they needed so many operators that no advantage over hand composition was gained. Hot-metal systems were developed at the end of the 19th century which finally solved the problems of combining typecasting, setting and distribution within a single system, and speeded up the process sufficiently that hand composition was laregly superseded. These methods enabled a single operator to set approximately three times as much text in the same time as a compositor working by hand, and removed the need for the time-consuming task of redistributing the type back into the cases after use.

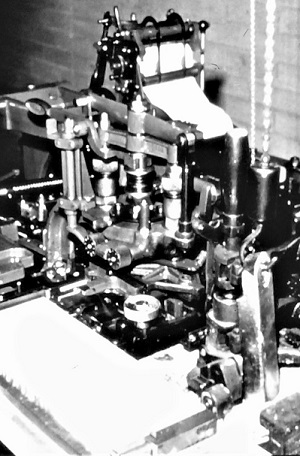

Linotype machines, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler (1854-1899) and James Clephane (1842-1910) were first demonstrated in 1886, and were manufactured commercially from 1890. Linotype combines setting and casting in a single ‘hot-metal’ machine, operated from a keyboard.

Monotype is the system invented by Tolbert Lanston (1844-1913) in the 1880s. The principles behind its operation were similar to those of the Linotype, but two separate units were involved, and letters and spaces were cast as individual pieces of type. The compositor sat at a keyboard, selecting the appropriate key for the characters and spaces in the text to be set. On completion, the paper roll was transferred to the caster operated by an attendant. The Monotype system was used mainly for book work, and from 1922, the Monotype Corporation employed the distinguished typographer, Stanley Morison (1889-1967) as an advisor and as well as introducing his most famous font, Times New Roman. The Corporation also commissioned high quality fonts from designers such as Eric Gill, Frederic Goudy and Bruce Rogers.

Monotype is the system invented by Tolbert Lanston (1844-1913) in the 1880s. The principles behind its operation were similar to those of the Linotype, but two separate units were involved, and letters and spaces were cast as individual pieces of type. The compositor sat at a keyboard, selecting the appropriate key for the characters and spaces in the text to be set. On completion, the paper roll was transferred to the caster operated by an attendant. The Monotype system was used mainly for book work, and from 1922, the Monotype Corporation employed the distinguished typographer, Stanley Morison (1889-1967) as an advisor and as well as introducing his most famous font, Times New Roman. The Corporation also commissioned high quality fonts from designers such as Eric Gill, Frederic Goudy and Bruce Rogers.

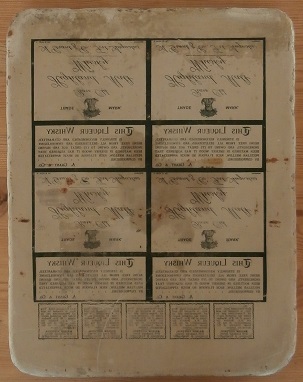

A third system of mechanical composition, which was used mainly for display work and jobbing printing, rather than newspaper and book printing. The Ludlow Typograph dates from the early years of the twentieth century and is best described as ‘semi-mechanical’. The matrices are assembled by hand into a composing stick, and justified in more or less the same way as type is set by hand composition, but instead of the completed stick being slid onto a galley, the composed stick forms a matrix from which the slug of type is cast in the caster, which ejects the trimmed slug into the galley. The matrices are then distributed by hand.

Mechanical composition using one or other of these systems formed the basis of most printing operations until the rise of phototypesetting in the 1960s and 1970s. You can watch film of Linotype (mainly used in newspaper printing) and Monotype (used in the book trade) machines in operation.

Photosetting or phototypesetting: these terms cover the arrangement of type made without the use of actual metal type. Experiments with photographic methods of reproduction avoiding the use of metal began in the early twentieth century, based on photographic methods of reproducing illustrations. Today such methods are based on the use of computers. The text can be typed in at a keyboard or scanned using optical character recognition technology.

Printing machines

The press in use in Gutenberg’s time was very similar to those used for cheesemaking, or to press grapes for winemaking, and was made of wood: it remained fundamentally unchanged for around 350 years. The forme of type was placed horizontally on the ‘bed’ of the press and the paper, one sheet at a time, was placed in a parchment covered frame called the tympan. The margins of the paper sheet were protected by a cut out sheet called a frisket. Once ink had been applied to the type, the tympan and frisket were folded down to lie flat over the forme, and the whole bed was slid under a flat plate, the platen, which was attached to a screw. Pressure was applied to this by the pressman pulling on a bar which acted on a screw and lowered the platen onto the paper and type. The amount of pressure that could be applied in this way was limited by the strength of the wooden frame.

One of the earliest improvements in letterpress printing at the beginning of the nineteenth century was the development of iron presses. The earliest British version, the ‘Stanhope’ was named after its inventor, Earl Stanhope, and the ‘Columbian’ was first constructed in Philadelphia by George Clymer shortly afterwards. The Albion press was developed in London in the 1820s, by R W Cope. There is more information on later developments on the Printing Machinery page.

The distinction between direct and offset printing

All printing methods are either direct or offset. Printing from forme to paper with no intervening stage, as in letterpress is a ‘direct’ printing system. Offset printing is planographic process (such as lithography) in which the printing plate makes an impression on a rubber sheet or roller, and the image is then transferred from the sheet or roller onto the paper. ‘Offset’ is usually associated with lithographic printing.

Originally lithography: originally this meant literally printing from the stone, a process discovered in 1796 by Aloysius Senefelder. The basis of this system of printing is the mutual repulsion of oil and water: a greasy image attracts the ink, which is repelled by the surface of the water bearing stone. Within a few years, Senefelder had discovered that the same principle could be applied to printing from metal plates: all subsequent developments of lithography, using metal and more recently plastic and polymer plates, have continued on the same principle.

The process of printing by lithography offset onto paper was developed by Ira W Rubel of New York in 1904, and over the following century it became the main printing process in use. The printing plates are usually metal (zinc or aluminium): the surface is not left smooth, but is given a finely grained texture, and when the inked image is printed down onto the plate, it is treated with chemicals to increase its tendency attract the greasy ink, while the non-inked areas are treated to increase their capacity to absorb water. The system is used for text and illustration, and for both monochrome and colour printing.

Photo-litho combines photography and lithography. A negative of the original text or illustration is made: a ruled screen is used for photographs of illustrations with tones. The negative is printed down onto a lithographic plate, and is printed by the offset litho process.

Illustrations

Woodcuts were the earliest form of printed illustrations. The design is drawn or traced in reverse on the plank grain of a block of soft wood, and is cut away by the artist using carving tools, so that the design is left in relief and the other areas area cut away. The result is bold lines with a white background.

The technique of wood engraving was developed by Thomas Bewick at the end of the eighteenth century. It differs from woodcuts in that the design is excised below type height. The surface of a block of hard wood is prepared and the design is then traced in reverse on the end grain. Steel graving tools of the kind used by metal engravers are used to excise the design: the surface of the wood receives the ink and the design is printed as a white design on a black background. Tones in the background can be achieved by the skilful use of lines and dots.

Engraving had been used as an intaglio printing process for many years before this. In intaglio processes, the design is cut into a metal plate, and the ink is held in these grooves, in contrast to relief printing processes such as letterpress and woodcut. These can be etched or engraved with sharp tools.

There are various types of etching, but the basis of all these methods is similar. A metal plate, usually copper or zinc is covered with a ground, the composition of which varies depending on the type of illustration required, and the back and sides of the plate are protected with a coat of varnish. The drawing is reproduced in reverse on the plate. The lines are then excised with a suitable tool to expose the metal, and the plate is dipped in a bath of acid to incise the lines of the design in the plate. Once the lines reach the required depth they are varnished over, and the plate can be dipped again until all lines have been incised to the required depth.

Photogravure is an intaglio process which originated in the work of Karl Klič (1841-1926) in the late 1870s. It was first introduced into the UK by the firm of T & R Annan of Glasgow in 1883. The image to be reproduced is photographed through a screen which marks the image into cells. From the negative, a continuous tone positive is then produced from the negative, and printed down onto a carbon tissue sheet. The image is then transferred to the printing surface and developed. A continuous tone print is then produced by printing from the plate once the design has been etched. The areas etched to the deepest levels, showed darkest, and the pattern of cells hold the ink. A ‘doctor blade’ removes the surplus ink from the surface of the plate. In the 1890s Klič adapted the process to allow for printing from rotary plates.

Newspaper illustrations were often produced using the half-tone process. The original is photographed through a ruled glass screen to produce a pattern of dots: the dots are of varying size, but equally spaced across the area to be printed. Once the negative has been developed it is printed onto the printing surface. The larger dots represent the darker shades, and when viewed normally produce the optical illusion of dark tones, but the dots can be seen through a magnifying glass.

The photo-engraving process is also known as ‘letterpress platemaking’ or ‘process engraving’ and can be used to reproduce any kind of original, in either monochrome or colour. The printing surface is in relief, and it is useful for illustrations which are closely combined with text.